Everybody likes a good story at the holidays. But just because it’s the holidays doesn’t mean that the hard-working vessels and crews of the US Coast Guard get any slack. Forty-nine years ago, in December 1967, the cutter STORIS and her crew were having a busy month, with search and rescue, a burial at sea and heavy weather complicating their efforts. A boatswain's mate aboard ship, BM3 Malcolm Robert Dick, recorded the experiences of the crew in a letter home to his parents. To look back, it's amazing to read of what serving on STORIS was like in heavy weather, even more so to realize it was "just another day at the office" for that brave ship and crew. Reposted with permission from Mr. Dick.

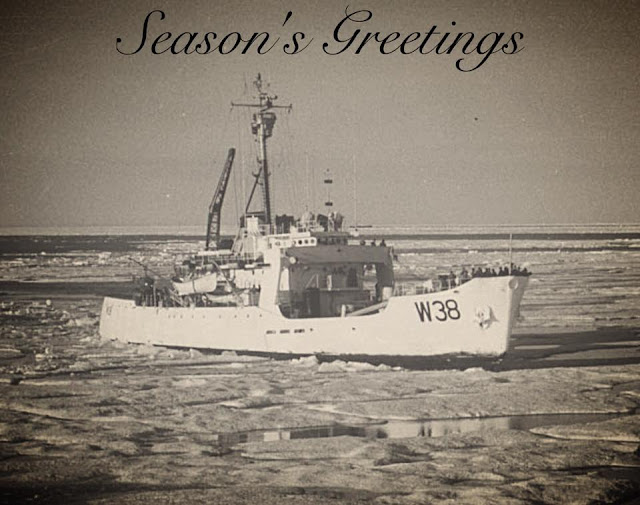

Accompanied by a STORIS Christmas card posted recently by Ray Rebmann, Jr. to his Fred’s Place Tribute Facebook page and a photo of STORIS taken from the stricken freighter STEEL FLYER by David Dent… More photos are on the way and can be posted once I have them in hand.

STORIS SEA STORY

Friday, 8 December 1967

Dear Mom and Dad,

CG Cutter STORIS is underway as before in the Gulf of Alaska some two hundred miles south of Kodiak. Our course is 185 degrees T, enroute an unknown position four hundred miles

off Kodiak to intercept and tow, standby or destroy a drifting Foss Tug barge. I am sitting on the mess deck writing this as we churn our way south.

We’ve been involved in this search and rescue (SAR) mission since 0500 Monday morning and probably will be involved with it until the middle of next week; it’s been one SNAFU after another. A combination of both in port and underway weather and events has made it difficult to write.

The last two weeks are good examples of why no one in his right mind would live on or near Kodiak Island. The wind rarely has dropped below 40 knots since Thanksgiving and last week was one solid williwaw. We guys in the deck department have been on the go checking mooring lines, replacing broken gear and generally keeping the ship where it should be at the fuel pier.

Maybe my mood is affected by the departure of – or soon to be departed – friends, Mike Usilton, Duane Kennedy and Steve Derry. Mike already left for 40 days leave, after which he goes to USCG Group Chincoteague about 50 miles from his home. Duane also is taking 40 days leave to Iowa and will return to duty at Portland, Oregon. Steve Derry, my bunkmate for the past year leaves in less than two weeks, and is headed for Texas. Man, I’m going to miss my buddies.

Ok, enough whining and back to the story…

The real wind began last Wednesday; it blew hard all night and quieted during the day. By Friday, it just got stronger as the day wore on. I had the duty Friday and stayed up late to watch mooring lines, all of which were taking a heavy strain. It blew 40 to 50 knots all day Saturday, and I stayed aboard ship. CITRUS returned Saturday with a full load of ice; her bow and everything forward of the bridge covered with six inches of ice. One of her crewmen slipped on an icy deck and somehow pulled his kneecap half off. I didn’t see him but understand he was in a lot of pain.

Mr. Rudolph called me to the wardroom early Sunday morning to give me the day’s skinny, since I had the duty. A large storm was working its way up the Aleutian Chain and two other systems were converging with it in the Gulf of Alaska. Nice. By 0900, Sunday, the wind was a steady 60-70 knots with gusts of 80-95 miles per hour, blowing us directly off the pier.

We had every mooring line, breast line and even tow hawsers set to keep us moored. By 1200, Sunday, winds were 80-90 knots with gusts to 120 +. Our anemometer only goes to 120. The winds ripped enormous sheets of spray off the bay, blasting over the ship, all in bright sunshine. At one point, the anemometer gauge unwound back to zero, a little strange. One glance up the mast told us why: the anemometer propeller was gone.

The Captain was aboard all day and spent much of that time on the bridge. He told us he probably would have gotten the ship underway and out of the harbor had he known the storm’s severity. I’m sure he was right but the pier looked pretty good compared to what the sea must’ve looked like in 120 knots of wind. However, there was no way we could get underway for sea, as we would have blown ashore had we tried to cast off.

All mooring lines were taught to the point of parting. Line 5 actually smoked it was so tight. We were afraid to slack any of the lines, but, in the end, had to adjust for the tides. By the way, it is also bitter cold, well below freezing.

CITRUS got a recall about noon, Sunday, but couldn’t get underway till 1500 when the wind slacked enough for her to spring off Marginal Pier. She had the opposite problem we did: the wind kept her plastered against the pier tight as hell. Her SAR was a fish boat that dragged anchor and was going aground in Puale Bay, across Shelikof Strait. The crew of the F/V ST ANTHONY reportedly was abandoning ship, near suicide in this weather. I say, “was” because it’s been almost a week now and CITRUS still is looking. Not much chance for the fish boat crew. CITRUS is looking for bodies now.

The wind hit again, harder, about chow time, Sunday, and blew with no let-up during the night. The entire deck crew was up all night keeping the ship secure. About 2100, I was down below, aft, and heard a tremendous, “BANG!” I scrambled into my foul weather gear (walking and standing on deck was impossible…you kind of pulled yourself from point to point) and hustled topside to see what had busted. It turned our line six, our stern line – ½”

cable –parted at the chock. The noise we heard below was the fairlead and parted line slapping the fantail deck. We replaced the cable with 5” nylon tow hawser, bowsed with chafing gear, and went below to find hot cocoa or coffee.

All was relatively quiet till 0400, Monday morning, when one of the guys (we took turns making rounds of the mooring lines) noticed the hawser parting at the chock. By the time we got dressed and on deck, one strand was taking the strain. We got the bad part aboard, the hawser reset, all just in time to go gulp more hot coffee and then prepare the ship to get underway for a SAR call. A little easier said than done, I might add…

This is where the story of the barge really begins (By the way, we’re back in port now and I’m writing this letter on the bridge. Everyone on the mess deck thinks I’m writing an encyclopedia.).

No one has time to eat and we have little desire, knowing what probably lies ahead at sea. We are anxious about the boat ride out to the barge, wherever the hell it is. STORIS is ready to get underway by 0800 but mooring stations aren’t set until 1015. There isn’t much point standing in the wind until we have a reasonable chance of getting away from the pier...one more reason why we will follow our skipper to hell and back. The Captain watches the wind for what seems like hours; when it lulls for a moment, we cast off everything holding us to the pier (including buoy chain by this time,) and depart the pier at close to full power, nearly washing poor old USS KODIAK ashore in the process. That’s the most excitement those guys have had in years!

The wind steadies to 40-50 knots once we clear Kodiak and we ride pretty well in a following sea. It is crystal clear and the sea surface is covered in six feet of tattered “sea-smoke,” and it seems like we are sailing over puffy cotton ripping by a lot faster than Storis will ever go. As we get further to sea, the seas rise considerably and sleep is out of the question. I have the mid-watch and get to lie in my rack for a while, anyway.

We find the barge with our radar about 0400 Tuesday and chase it till noon. The weather is deteriorating (yes, it actually gets worse) and it is impossible to put a boat over the side to transfer towing gear to the barge. About noon, it becomes immaterial as we are ordered to secure from our barge to assist Alaska Roughneck, the tug that lost the barge. She evidently is making heavy weather of it and in her skipper’s words, “Don’t know exactly where we are.” So, we are supposed to find and assist these guys somewhere in

thousands of square miles of really ugly ocean. Jeez.

We finally get RDF bearings on Roughneck and spend the rest of the day cruising around the North Pacific looking for him. By Wednesday morning, we are still looking, with seas building into the significant class. Did I add that no one is able to sleep? Or get hot meals?

A CG aircraft finally finds Roughneck 50 miles offshore and gives us the position, which is a lot closer to Kodiak than we are. That puts our course right into steep, nasty seas that later cause us to come about and run with the seas for a time to fix stuff that came adrift earlier. Cargo secured on the well deck washes from its moorings, the LCVP is full of ice and salt water; the anchors are loose in their hawse pipes, a block on the starboard ready

boat fails, allowing the strongback to fall to the deck; and the port well-deck door is broke, so we tie it shut and finally close fresh air vents on the 01 deck that allow salt water into parts of the ship not built for that kind of foolishness. The power of water is amazing.

We locate the tug on radar about midnight, just as he pulls into a nice calm bay on Sitkinak Island. We are ordered to return to Kodiak, sick of the barge, the tug, the North Pacific, and everything associated with this SAR. Not to mention we are going on five days with little or no sleep and mainly sandwiches for food.

We arrive Kodiak at 0900 Thursday morning, only to be told we must immediately get underway to recover Mr. Foss’s goddamned barge. The skipper’s reaction is priceless. He strings words together to describe the situation in terms most lumberjacks would admire. We couldn’t agree more. We also wonder why Mr. Foss’s own tugboat isn’t assigned the job.

We are underway, again, by Thursday, noon, with an additional passenger, a recently deceased Captain Frank Curry, who evidently expressed a desire to be buried at sea.

It might have been okay if the body had come complete with box or casket, but no such luck. Capt. Curry arrives trussed up in a canvas bag appropriately embalmed and weighted with 350 pounds of lead. Several of us seamen cart the departed Captain from a station wagon to the fantail where it falls to me to secure the body against the superstructure. We Bosuns make our duly appointed rounds at night, which requires us to check and see if the Captain is still with us. Brrrrr.

Friday morning finds us underway as before in deteriorating (I hate that word) weather, building seas, snow, wind, all the ingredients needed to send Capt Curry to his reward. We aren’t in a giant hurry to find the barge, which, by this time drifts 500 miles out, so we stop and commit Capt Curry to the deeps. All hands muster on the fantail and I have the dubious honor of being a pallbearer. The skipper reads from his seaman’s bible and, “commits the body unto the deeps.” Splash...

It will be a very, very cold day before they do that to me.

Seas are rough, but we search the entire day for the damned barge. CG Station Kodiak tries to send out an airplane to help us search but the weather is bad. No kidding. We figure that out all by ourselves. By now the barge could be almost anywhere in the North Pacific.

The weather improves on Sunday, enough so that a CG amphibian (we call them “Fighter Bombers”) locates the barge at 1400 hours. It is 80 miles NE of us from a poor LORAN fix by the aircraft. Our airborne friend loses an engine and returns to Kodiak for afternoon tea. Needless to say, our search is fruitless. The plane returns on Monday and finds the barge some 50 miles NE of us.

It’s pretty ironic that the barge drifts from just off Sitkinak to 500 miles at sea and now is drifting back towards Kodiak. Seems the only way for Storis to get out of the North Pacific is to follow the barge ashore.

We prepare to take the barge under tow all day Monday, which entails raising the A/C crane to its full vertical position, then rotating it 180 degrees to secure it to the mast and a bulkhead. It is a ticklish operation at sea, because the lifting cables go way slack in the fairleads allowing the cables to jump the shivs if things go wrong. We know that, but we need the crane out of the way.

I am on the well deck about 1115, looking aft down the starboard side of the 01 deck as the ship takes a deep starboard roll. As it reaches the depth of its roll, I hear a loud “BANG,” and watch the A/C fall outboard over the starboard side. I don’t see it hit the deck but I sure as hell hear and feel it, as the ship vibrates for several seconds. It takes me about two seconds to reach the fantail, where I see the A/C draped over the starboard warping winch, hanging outboard, dragging in the water. By some miracle, no one is hurt although there are several white faces staring over the side.

As far as we can tell, the lines slipped their shivs and jammed so they were immovable. The ship’s hard roll caused the crane to move on its base turntable, come up hard on the now immovable cables, cutting them like butter, sending the crane to the deck. Really hard. It is bent and twisted, hanging over the side, severed lines hanging; every time the ship rolls to starboard, the crane groans and shifts from the force of the water. It is only a matter of time till something really bad happens like a line getting in the screw. That is big trouble. Over the next hour, our First Class Boats, Vandervest, crawls out on the crane (hanging over the side in a substantial sea) where he clips together the topping lift line so we can raise the crane from the water. I volunteer to operate the controls and raise the crane to the deck, which goes without incident. But not without a couple of fervent prayers for those six cable clips! We all had to write statements and I had to wait a few minutes for my hands to quit shaking.

We finally arrive at the barge by 1500, an hour later than planned. The ready boat is lowered, no mean feat in the large swell and sea that is running. The boat crew is supposed to secure a light line on the barge’s towline so we could bring it aboard and use the barge’s towline to tow the barge. Cdr. Hein, our XO, brings the ship close aboard the barge on our port side to assist our boat crew in the towline exchange from the small boat to the ship.

Good plan in theory. We are all on the port side watching the operation when it quickly becomes obvious the barge is setting down on Storis a whole lot faster than anyone anticipates. For a moment, it looks like the port ready boat davits; along with any stray ship parts on the port side will be forcibly removed. By the time Storis clears the barge, there are maybe ten or twelve feet separating us. Remember, there is a large swell and six more

feet of wind waves on top of the swells. One moment, we are many feet above the barge; the next moment, the barge seems ready to launch itself onto our fantail. All of us on the fantail watch it all unfold, fascinated, from the starboard side.

I am responsible for getting a heaving line, with messenger line, to the ready boat, which I do. The ready boat crew intends to put a sling under the barge’s tow hawser and reave the messenger line through the tow straps. We would take aboard the messenger till we retrieve the barge’s 3” Manila hawser (none too big for an ocean going barge, by the way), which we will bring aboard to our port warping winch, allowing us to secure the towline to our main tow bitt. Hope that makes some sense. You probably had to be there to understand it.

Seas are rising fast and it is getting dark. We do not recover the barge’s towline and still have a boat away in seas quickly getting nasty. The prudent decision is to secure, which we do. Too bad. We could’ve done it. I learned a lot even if we didn’t capture our barge. The next chore is to recover the ready boat in high seas at dark. Friedenbloom, the boat cox’n, receives the painter and orders the falls secured to the ready boat, just as an enormous swell shoves the boat away from the ship. The ship just as suddenly (it’s amazing how fast this all happens) lurches to starboard, leaving the ready boat instantly suspended in twelve or fifteen feet of air, slamming the boat against the ship, sending it under the hull, almost out of sight of those of us on deck.

Just as quickly, the ship rolls back to port, squirting the boat out from under the ship’s hull. There is much crashing, banging, lines thrashing, falls and davits bending and groaning, plus all the boat/ship collision noises coming from below us. As soon as the boat reappears, it is hoisted aboard with six wet, shaking souls mighty glad to be back aboard Storis. The barge will wait for another day.

The next day, Tuesday, 12 December, I get up at 0330 for my watch after spending five or six hours being tossed around in my rack. Sleep is impossible. The wind is 45-55 knots and rising quickly; the seas prohibit putting a boat over the side to recover the barge’s towline. By 0800, all hell breaks loose: a Navy plane in our vicinity loses two of four engines and plans to ditch near us. That’s a really bad idea with high seas in our vicinity. A freighter, SS Steel Flyer, reports losing its rudder in heavy seas 250 miles SW of our position at almost the same time.

Evidently the plane figures we are a poor bet and does something else; we head for Steel Flyer. She is at least 30 hours away and it is apparent the weather is taking a serious turn for the worse. The skipper estimates sea height at 65’ during the worst part of the day. No one argues with him about it. They defy adequate description.

A few words about life on USCGC Storis in bad weather: it’s not a lot of fun. The simple act of walking is an art, sometimes impossible, when it’s rough. At times, it IS impossible. Today, Tuesday, we are underway as before, headed yet further into the North Pacific to render assistance to Steel Flyer.

The weather steadily deteriorates overnight and the seas by mid-morning are huge. Enormous. Staggering. I can’t begin to describe their ferocity. We head into the seas, turning for 13.5 knots, our service speed, making perhaps 3 knots. The ship is pounding heavily, lurching, crashing, no one able to take more than few steps without grabbing something, smashing into a bulkhead, getting thrown across a compartment or passageway. Noise is everywhere; wind, the seas roaring over the ship, the ship, itself, stuff falling, guys groaning, swearing. The ship frequently stops, dead, as it smacks headon into a huge sea. Everything else continues forward until it or they encounter something solid. The entire ship shudders, surges upward at a dizzying speed, then falls off, usually canted to one side or another, and crashes into the bottom of the wave, waiting to do it all over again. Man, it gets old.

On the bridge, forward visibility is limited to maybe a quarter mile but it doesn’t matter. All we can see through the spray and snow is a forest of enormous waves with equally huge breaking crests, all coming dead at the ship, seemingly bent on killing our ship and us along with it. The forward third of the ship routinely disappears underwater. One minute in this stuff is an eternity.

Somewhere in all of this, noon chow is piped and we dutifully trundle to the mess deck and gulp what the poor cooks prepare. It’s funny…you would think food would be the last thing on our minds but most of us are used to the violent motion and go on with life as best we can. Including food. You know me!

The cooks deserve special mention because they do their best to prepare decent meals in an ancient galley under conditions that defy description. The simple act of heating soup becomes a hazardous chore. We bitch a lot about our food, but generally are well fed, three hot meals whenever possible, which means in all but the worst weather. The messdeck portholes, today, look like commercial washing machines. They normally are 10’ above the waterline but on days like today, they often as not are under water.

Most folks disappear after chow and quarters. I make a giant roast beef son-of-a-bitch (Pacy Handlovsky’s description of a roast beef sandwich) and head for the main hold, which is forward and rough riding. The bosses won’t be down there this day. I crawl down the ladder and inch my way forward to the watertight door leading to the hold. Ducking through, without getting bashed by the heavy door (timing is important), I scuttle across the hold to the bosun’s locker, where a chair is tied to the bulkhead.

I settle in to chow down on my roast beef son of a bitch when a bunch of things happen all at once: the ship rises and just keeps going up. The sea must be beyond enormous. Swede Hanson is crossing the main hold and another guy is stepping across the coaming at the watertight door.

What happens next is unforgettable. The ship abruptly stops its ascent and falls off to starboard. In a millisecond, we are falling so fast that I float out of my chair; Swede levitates off the deck and the guy stepping through the watertight door floats over the coaming. No one has time to think or react…just imprint what happens. We hit bottom with unbelievable force. I thump into my chair, Swede flies across the entire hold into a batch of fenders and all hell breaks loose. The ship vibrates, resonates, flexes. We watch our great big home shudder from the force of hitting the bottom of that sea. We think the forward half of the ship has torn away from the rest of the ship. Stuff flies everywhere. The noise is more than deafening; it assaults us from every direction. We are scared stiff.

After an eternal second or two, the ship rights herself and rises to meet the next sea. We are thoroughly frightened and want nothing more than to be somewhere else on earth. Anywhere else on earth. I read somewhere there are no atheists in a foxhole. I know what the guy means.

Shortly after that escapade, the ship’s PA tells us we were coming about to run with the seas and to stand by for heavy rolls. In sixty-five foot seas, that could be a life or death decision. We all painfully are aware the Captain is taking a necessary action to ensure we live to sail another hour, another day. It isn’t a great choice but if the Old Man believes it gives us the best chance of survival, it is ok with us. Not that he asks our opinion….

All this is going on while I continue to eat my sandwich in the bosun’s locker, six feet below water line. I guess we weren’t scared enough to quit eating! It is interesting, however, to hear the story of how the skipper brings the ship about. A Quartermaster named Carney tells the story best: Carney is at the engine telegraph, and the skipper is watching the seas. The skipper is quiet, apparently calm. How he can be calm in situations like this is beyond me.

Carney is anything but calm but also watches the seas, knowing what will happen if things don’t go right. The skipper waits for several minutes, and then waits some more. He’s watching wave patterns, waiting for a series of big seas, after which a series of smaller seas should follow. The key word, of course, is “should.” After what seems like an eternity, the skipper gives the command (Cdr. Hardy has assumed the “con,” meaning he is in direct command of the ship. That happens only in moments of duress or entering/leaving harbor) to come about and concurrently asks for full power. The helm is down, the engines at full power before the words are out of his mouth. Then begins the wait. The big Cooper Bessemer engines rumble and the ship vibrates with increased RPM’s. The ship begins to ever so slowly turn. It’s agonizing. One hundred people are riveted to whatever place they occupy, thinking, saying, “C’mon, baby. C’mon, c’mon, c’mon!” I assume everyone, including me, is asking God for a little help, too. The ship heaves over in the seas, as she begins her ponderous turn. Carney is thinking, “Go, baby. Goddamn, give me an oar; Give me anything to make this tub turn faster. Go, baby, pleeeeaaase.”

The Captain has chosen his timing with skill borne of forty years at sea. We come about and steady up on a course with the seas. Suddenly the ride is smooth, or at least it seems so. The waves are so big the ship rides up and over with relative ease and slides down the other side like a surfer. That’s the catch. Running with big seas is a much easier ride but the ship could surf, broach and capsize if any number of things goes wrong. The helmsman must really be on his toes and the ship must go fast enough to maintain steerage but not so fast that we lose control on the downhill slide.

I wander up to the bridge after things settle down and stare in awe at the seas. Lord, those big seas are running by us ABOVE the bridge. The overhanging crests crash around us, over us, longside us, but we remain afloat and moving. It is a brutal but beautiful scene, right out of a book. But it is all too real. Some day, this will make a great sea-story but I’d rather be anywhere else, right now.

We run with the seas till the storm abates later that evening, when we came about and continue our journey to Steel Flyer. Oh, by the way, this is the ONLY time we’ve ever turned to run with the seas on a SAR. We’re proud of that.

Steel Flyer is a C-3 freighter (so I’m told), 470 feet long and 8400 gross tons, displacement, a lot bigger than our 230’ and 2300 tons. She is in ballast, riding light and high. I’ll bet she had fun on Tuesday. Evidently she could maintain some steerage way using her engines. We are underway all Wednesday and reach Steel Flyer at 1900 in the dark, with a light sea and enormous swell. Two tugs are enroute, one from Seattle, the other from Adak. Get this: the freighter skipper declines our offer to tow because, he says, we are “too little,” and the danger to us would be too great. That damages our egos but saves us a lot of work. The master must’ve been quite a seaman. He had no LORAN so was doing all his navigation by celestial and DR, and doing a very good job of it as his fixes were accurate given conditions. Roughneck’s skipper could’ve taken some navigation lessons from this guy. His ship also survived high seas with no rudder, another impressive feat of seamanship.

We stand by the freighter all Wednesday night and Thursday, and have a potentially serious boiler fire Thursday night. Seems the skipper was playing poker with the chiefs, left for a trip topside and discovered the smoking boiler. Bet the snipe watch standers got their butts chewed! Navy tug, Chanowac, a 210 ocean going tug, arrives 0300 Friday morning and the commercial tug, Sampson, is due Sunday, from Seattle. Seas continue to abate and we are released later Friday to go home. Halleluiah! We have a moderate sea off our port quarter, and are making 14 + knots towards Kodiak. “The Rock” will look good after this misbegotten series of events.

Even after the past two weeks, I marvel at the sea’s beauty. Friday night is clear; the moon full, save for a few fleecy clouds racing across the sky. The moon silvers the clouds and a light sea breaks the reflected moonlight into millions of silver shards. Every ripple is like a silver spark. I stay on deck for half an hour watching the light show till I get cold and go below to warm up. It’s still November in the North Pacific.

Mr. Foss’s barge is still somewhere “out there,” and we hold our breath. Maybe it sank… Supposedly a commercial tug is searching for it and we wish them well. We never want to see it again. .

It’s not too long till Christmas and we will be here, or at sea. I really miss you guys and can’t wait till I rotate next July. Seems like forever. Our weeks at sea are three days long: yesterday, today and tomorrow. Nothing further back or ahead matters. Just yesterday, today and tomorrow. July seems like a million years away. Maybe that’s just the way it has to be to maintain some sort of sanity in our world.

Merry Christmas from the USCGC Storis!

Bob